“Corpse Bride” is a macabre fairy tale musical filled with dancing skeletons, a maggot who serves as the “Corpse Bride” equivalent of Jiminy Cricket, and rollicking musical numbers from ex-Oingo Boingo front man and frequent Tim Burton collaborator, Danny Elfman. But above all else, “Corpse Bride” is an enchanting wild ride through the land of the dead, infused with Tim Burton’s unique brand of wit and humor, and brought to life by the vocal talents of Johnny Depp, Helena Bonham Carter, and Emily Watson.

Burton, co-director Mike Johnson, and screenwriters John August, Caroline Thompson and Pamela Pettler don’t bother burying the fact “Corpse Bride” is all about love. Sure, there are dance numbers and adult-oriented jokes, but the fact that this is actually a moving romantic tale is always kept front and center.

After being attacked and killed while waiting for her fiancée in a dark, scary forest, the Corpse Bride is bound and determined to never, ever be left again. An opportunity for everlasting happiness suddenly presents itself when Victor, a humble, shy, and extremely uncertain of himself groom-to-be wanders into her forest while practicing his wedding vows.

Victor finally gets the lines down pat but soon discovers that’s not necessarily a good thing. The wedding ring he intended to place on his bride-to-be’s finger winds up on the protruding skeletal finger of the Corpse Bride. That act, when taken in concert with Victor’s uttered vows, is enough to pull the Corpse Bride up out of the frozen ground and into Victor’s surprised embraced. Victor may have wanted to get married, but he definitely didn’t want to take a wedding dress-clad skeleton with an eyeball that pops out at the most inopportune times as his wedded wife.

Because “Corpse Bride” is actually a feel-good love story only barely disguised as a gothic horror film, Burton and Co throw in plenty of jokes but never let the mood get too dark. Though I still consider “Corpse Bride” a bit too scary for kids, there were a couple in the preview audience who seemed to really get into the dance numbers and the adorable skeleton dog (it does sound weird but he is a cutie - even without fur).

I love the fact Burton chose to make the land of the dead vibrant and alive while portraying the world inhabited by the living as one of dull colors, gloomy surroundings and repressed people. The dead heads are much more fun and lively than those with still-beating hearts. While the majority of those still living care more about money and material possessions, in the land of the dead friends are loyal and people (read ‘skeletons’) care about what happens to each other.

“Corpse Bride” looks absolutely gorgeous. The colors are crisp and clean and practically leap off the screen. Coming in at around 85 minutes, “Corpse Bride” never drags but instead moves swiftly through the story, delivering laughs along with a sweet message about the power of love.

Corpse Bride review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:41

(A review of Corpse Bride)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:41

(A review of Corpse Bride) 1 comments, Reply to this entry

1 comments, Reply to this entry

Sleepy Hollow review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:39

(A review of Sleepy Hollow)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:39

(A review of Sleepy Hollow)The year is 1799 and ''the millennium is almost upon us,'' according to the newly dashing Ichabod Crane played by Johnny Depp in Tim Burton's enthusiastically bleak new movie. And speaking of dashing, when Ichabod gallops north from New York City, he rides up the west bank of the Hudson River although the village of Sleepy Hollow is on the east. But an ornate visual fantasy of Mr. Burton's can be expected to make its own rules, and ''Sleepy Hollow'' does that with macabre gusto. His idea of a beautiful day may be somebody else's nuclear winter, but Mr. Burton eagerly brings his visions of sugarplums to the screen.

So when it comes to appearances, this dark, shivery ''Sleepy Hollow'' manages to be as distinctively Burtonesque as ''Edward Scissorhands'' or ''Batman.'' Offering a serenely unrecognizable take on Washington Irving's story and its famously unlucky schoolteacher, the film brings its huge reserves of creativity to bear upon matters like the severing of heads. Quaint Dutch burghers of the Hudson Valley could have bowled ninepins throughout Rip Van Winkle's sleep-in with the supply of decapitated heads sent flying here, even if Mr. Burton handles such sequences with his own brand of wit. Shot 1: Sword approaches victim. Shot 2: Blood splashes Ichabod's glasses. Shot 3: Head rolls away. Shot 4: Body pitches forward. Pause for laugh.

History will recognize the rich imagination and secret tenderness of Mr. Burton's best films. (From a purely technical standpoint, as in the award-ready cinematography of Emmanuel Lubezki, this grimly voluptuous ''Sleepy Hollow'' must be one of them.) But it will also raise the question of what we were smoking during this period of infatuation with grisliness on screen. It is not unreasonable to admire Mr. Burton immensely without wanting to peer at the exposed brain stems of his characters, but ''Sleepy Hollow'' leaves no choice. As written by Andrew Kevin Walker, who took off Gwyneth Paltrow's head in ''Seven'' and apparently considered that small potatoes, ''Sleepy Hollow'' turns the tale of the Headless Horseman into the pre-tabloid story of a rampaging serial killer.

There are reasons to be troubled by this, and they aren't about squeamishness. Mr. Walker's credits also include ''Fight Club,'' a genuinely daring effort to make sense of the violent impulses of buttoned-down young men, and to plumb those dangers found at the nexus of popular culture and political fanaticism. That, at least, had the hallmarks of something different, and it involved a much lower body count than the one racked up by the Headless Horseman. But ''Sleepy Hollow,'' in the guise of an exotic fable and horror-film homage, offers little such ballast. For all its visual cleverness, it's much more conventionally conceived than Mr. Burton's admirers would expect.

Even birds nesting in one of the film's vast, wintry indoor sets found themselves trying to get away, moving into the only blossom-filled backdrop that ''Sleepy Hollow'' uses (for brief fantasy scenes). But the bulk of the film unfolds in a forbidding, fairy-tale village and forest that are as ambitious as the Gotham City of ''Batman.'' It is here that Ichabod, who now has a faintly English accent and Mr. Depp's playful charisma, is sent to solve a series of murders and to find that everyone in Sleepy Hollow looks mildly suspect. It is also here that he learns of the vengeful headless Hessian (Christopher Walken in redundant fright makeup) who is the town's main tourist attraction.

Using a color palette more often associated with stories of the gulag, ''Sleepy Hollow'' creates a landscape so daunting that even a large tree bleeds. At moments like the one revealing the tree's bloody secret, and in a couple of incidents involving witchcraft, Mr. Burton's film delivers a scare or two, but most of it is too tongue in cheek for that. As this film's Ichabod conducts a Holmesian murder investigation and even unearths a village conspiracy, he has much better luck with Katrina Van Tassel than any traditional Ichabod ever did. Katrina is played photogenically by Christina Ricci, who gets through the film gamely while remaining very much a sardonic creature of her own time.

An impressive cast shows off Colleen Atwood's sumptuous costumes and delivers dialogue, some apparently worked on by Tom Stoppard, sometimes graced with a clever edge. Miranda Richardson swishes dangerously through the proceedings as Katrina's obviously wicked stepmother, while the town elders include Michael Gough, Michael Gambon and Jeffrey Jones. The horror patriarch Christopher Lee is here, as well he ought to be. And Marc Pickering plays the teenage sidekick whom Ichabod cautions, as he might the audience, with ''I hope you have a strong stomach.''

Among the many scenes of cheeky mayhem, one finds a little boy cowering beneath floorboards while the Horseman harvests the heads of his parents. In case you were thinking of taking the children.

NYT

So when it comes to appearances, this dark, shivery ''Sleepy Hollow'' manages to be as distinctively Burtonesque as ''Edward Scissorhands'' or ''Batman.'' Offering a serenely unrecognizable take on Washington Irving's story and its famously unlucky schoolteacher, the film brings its huge reserves of creativity to bear upon matters like the severing of heads. Quaint Dutch burghers of the Hudson Valley could have bowled ninepins throughout Rip Van Winkle's sleep-in with the supply of decapitated heads sent flying here, even if Mr. Burton handles such sequences with his own brand of wit. Shot 1: Sword approaches victim. Shot 2: Blood splashes Ichabod's glasses. Shot 3: Head rolls away. Shot 4: Body pitches forward. Pause for laugh.

History will recognize the rich imagination and secret tenderness of Mr. Burton's best films. (From a purely technical standpoint, as in the award-ready cinematography of Emmanuel Lubezki, this grimly voluptuous ''Sleepy Hollow'' must be one of them.) But it will also raise the question of what we were smoking during this period of infatuation with grisliness on screen. It is not unreasonable to admire Mr. Burton immensely without wanting to peer at the exposed brain stems of his characters, but ''Sleepy Hollow'' leaves no choice. As written by Andrew Kevin Walker, who took off Gwyneth Paltrow's head in ''Seven'' and apparently considered that small potatoes, ''Sleepy Hollow'' turns the tale of the Headless Horseman into the pre-tabloid story of a rampaging serial killer.

There are reasons to be troubled by this, and they aren't about squeamishness. Mr. Walker's credits also include ''Fight Club,'' a genuinely daring effort to make sense of the violent impulses of buttoned-down young men, and to plumb those dangers found at the nexus of popular culture and political fanaticism. That, at least, had the hallmarks of something different, and it involved a much lower body count than the one racked up by the Headless Horseman. But ''Sleepy Hollow,'' in the guise of an exotic fable and horror-film homage, offers little such ballast. For all its visual cleverness, it's much more conventionally conceived than Mr. Burton's admirers would expect.

Even birds nesting in one of the film's vast, wintry indoor sets found themselves trying to get away, moving into the only blossom-filled backdrop that ''Sleepy Hollow'' uses (for brief fantasy scenes). But the bulk of the film unfolds in a forbidding, fairy-tale village and forest that are as ambitious as the Gotham City of ''Batman.'' It is here that Ichabod, who now has a faintly English accent and Mr. Depp's playful charisma, is sent to solve a series of murders and to find that everyone in Sleepy Hollow looks mildly suspect. It is also here that he learns of the vengeful headless Hessian (Christopher Walken in redundant fright makeup) who is the town's main tourist attraction.

Using a color palette more often associated with stories of the gulag, ''Sleepy Hollow'' creates a landscape so daunting that even a large tree bleeds. At moments like the one revealing the tree's bloody secret, and in a couple of incidents involving witchcraft, Mr. Burton's film delivers a scare or two, but most of it is too tongue in cheek for that. As this film's Ichabod conducts a Holmesian murder investigation and even unearths a village conspiracy, he has much better luck with Katrina Van Tassel than any traditional Ichabod ever did. Katrina is played photogenically by Christina Ricci, who gets through the film gamely while remaining very much a sardonic creature of her own time.

An impressive cast shows off Colleen Atwood's sumptuous costumes and delivers dialogue, some apparently worked on by Tom Stoppard, sometimes graced with a clever edge. Miranda Richardson swishes dangerously through the proceedings as Katrina's obviously wicked stepmother, while the town elders include Michael Gough, Michael Gambon and Jeffrey Jones. The horror patriarch Christopher Lee is here, as well he ought to be. And Marc Pickering plays the teenage sidekick whom Ichabod cautions, as he might the audience, with ''I hope you have a strong stomach.''

Among the many scenes of cheeky mayhem, one finds a little boy cowering beneath floorboards while the Horseman harvests the heads of his parents. In case you were thinking of taking the children.

NYT

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Big Fish review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:34

(A review of Big Fish)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:34

(A review of Big Fish)Tim Burton -- who made ''Pee-Wee's Big Adventure,'' ''Edward Scissorhands'' and the first two ''Batman'' movies, among others -- is surely one of the most prodigiously imaginative filmmakers around. His best movies glide effortlessly from devilish whimsy to startling perversity, and even when his storytelling falters his inimitably strange visual sensibility leaves its haunting, humorous traces on the memory.

There are, true to form, some startling scenes in his new movie, ''Big Fish'': the hero's arrival in a hamlet called Specter, where the streets are paved with grass and the citizens are always barefoot; his encounter with a witch (Helena Bonham Carter) whose glass eye can reveal the future; his appearance on a campus quadrangle carpeted with daffodils.

The movie also includes, for good measure, a giant named Karl, a squad of circus folk (led by Danny DeVito), a pair of conjoined Korean twins and some menacing, anthropomorphic trees. The theme of ''Big Fish,'' adapted by John August from the novel by Daniel Wallace, is the transforming, sometimes bewildering power of the imagination, which would seem to be a natural subject for Mr. Burton. But the most curious thing about this magical-realist fable, which opens today in New York, Los Angeles and Toronto, is how thin and soft it is, how unpersuasive and ultimately forgettable even its most strenuous inventions turn out to be.

The hero is Edward Bloom, a traveling salesman, who, though he comes from a small town in Alabama, is played as a young man by Ewan McGregor, who is Scottish, and in his later years by Albert Finney, who is English. These two actors (their Southern accents, by the way, are not bad at all) share a robust sense of mischief that overcomes their physical differences. You have no trouble imagining Mr. McGregor mellowing and thickening into Mr. Finney.

Edward, who personifies the bumptious, mythic American life force, is devoted to shading and embellishing the truth. He is an inveterate spinner of what Tom Sawyer, one of his literary ancestors, liked to call stretchers. Edward's oft-repeated, never-verified tall tales, including his signature yarn, the fish story that gives the movie its title, are endlessly charming, except to his son, Will (Billy Crudup), who finds them so exasperating that he stops speaking to his father for several years.

Will is a news-agency reporter in Paris, a suitably empirical profession for the rebellious son of a fabulist father. A phone call summons Will back home to Alabama for a deathbed reconciliation, during which Edward elaborates his fairy-tale biography. In his telling, the usual stations of the life cycle -- departure from home, courtship (of the lovely Alison Lohman, whose character ages gracefully into Jessica Lange), fatherhood, an accidental foray into crime -- become wild episodes in a sprawling picaresque adventure. If only. Even though Will's warmhearted French wife (Marion Cotillard) and his soft-eyed mother (Ms. Lange) hang indulgently on Edward's every word, his stories are so labored, so self-flattering and ultimately so pointless that it is hard not to feel some sympathy for Will, who grew up in his father's shadow and, for much of his childhood, in his absence.

From time to time, a glimmer of real drama shines through all the twinkly sentiment. The conflict between father and son is the most, perhaps the only, believable element in the story, but the movie is so thoroughly bewitched by Edward that it makes Will look like a cold fish who stubbornly refuses to accept his father for what he is. At one point, Edward's doctor (Robert Guillaume) suggests that Edward's stories are preferable to the banal facts of ordinary life. Wouldn't Will prefer to believe that, on the day of his birth, his dad was subduing a legendary catfish rather than selling household gadgets in Wichita?

The movie insists that the only possible answer is yes, and thus chooses maudlin moonshine over engagement with the difficulties of real life, which is exactly the choice Edward has made. Its vision of America, of the South in particular, during the last four decades or so has been scrubbed clean of any social or political messiness, much as the life of the Bloom family, notwithstanding Will's poutiness, has been burnished to a warm, happy glow. In their eagerness to celebrate Edward's grand spirit, the filmmakers wind up diminishing it, declining to explore the causes or the costs of his addiction to fantasy.

In the past Mr. Burton's images have had a touch of the uncanny, as though they were windows onto the scary, marvelous landscape of the unconscious. ''Big Fish'' lacks the resonance of his earlier work partly because this time the bright, antic inventions are a form of denial. The film insists on viewing its hero as an affectionate, irrepressible raconteur. From where I sat, he looked more like an incorrigible narcissist and also, perhaps, a compulsive liar, whose love for others is little more than overflowing self-infatuation. But all this might be forgivable -- everyone else in the picture thinks so -- if Edward were not also a bit of a bore.

NYT

There are, true to form, some startling scenes in his new movie, ''Big Fish'': the hero's arrival in a hamlet called Specter, where the streets are paved with grass and the citizens are always barefoot; his encounter with a witch (Helena Bonham Carter) whose glass eye can reveal the future; his appearance on a campus quadrangle carpeted with daffodils.

The movie also includes, for good measure, a giant named Karl, a squad of circus folk (led by Danny DeVito), a pair of conjoined Korean twins and some menacing, anthropomorphic trees. The theme of ''Big Fish,'' adapted by John August from the novel by Daniel Wallace, is the transforming, sometimes bewildering power of the imagination, which would seem to be a natural subject for Mr. Burton. But the most curious thing about this magical-realist fable, which opens today in New York, Los Angeles and Toronto, is how thin and soft it is, how unpersuasive and ultimately forgettable even its most strenuous inventions turn out to be.

The hero is Edward Bloom, a traveling salesman, who, though he comes from a small town in Alabama, is played as a young man by Ewan McGregor, who is Scottish, and in his later years by Albert Finney, who is English. These two actors (their Southern accents, by the way, are not bad at all) share a robust sense of mischief that overcomes their physical differences. You have no trouble imagining Mr. McGregor mellowing and thickening into Mr. Finney.

Edward, who personifies the bumptious, mythic American life force, is devoted to shading and embellishing the truth. He is an inveterate spinner of what Tom Sawyer, one of his literary ancestors, liked to call stretchers. Edward's oft-repeated, never-verified tall tales, including his signature yarn, the fish story that gives the movie its title, are endlessly charming, except to his son, Will (Billy Crudup), who finds them so exasperating that he stops speaking to his father for several years.

Will is a news-agency reporter in Paris, a suitably empirical profession for the rebellious son of a fabulist father. A phone call summons Will back home to Alabama for a deathbed reconciliation, during which Edward elaborates his fairy-tale biography. In his telling, the usual stations of the life cycle -- departure from home, courtship (of the lovely Alison Lohman, whose character ages gracefully into Jessica Lange), fatherhood, an accidental foray into crime -- become wild episodes in a sprawling picaresque adventure. If only. Even though Will's warmhearted French wife (Marion Cotillard) and his soft-eyed mother (Ms. Lange) hang indulgently on Edward's every word, his stories are so labored, so self-flattering and ultimately so pointless that it is hard not to feel some sympathy for Will, who grew up in his father's shadow and, for much of his childhood, in his absence.

From time to time, a glimmer of real drama shines through all the twinkly sentiment. The conflict between father and son is the most, perhaps the only, believable element in the story, but the movie is so thoroughly bewitched by Edward that it makes Will look like a cold fish who stubbornly refuses to accept his father for what he is. At one point, Edward's doctor (Robert Guillaume) suggests that Edward's stories are preferable to the banal facts of ordinary life. Wouldn't Will prefer to believe that, on the day of his birth, his dad was subduing a legendary catfish rather than selling household gadgets in Wichita?

The movie insists that the only possible answer is yes, and thus chooses maudlin moonshine over engagement with the difficulties of real life, which is exactly the choice Edward has made. Its vision of America, of the South in particular, during the last four decades or so has been scrubbed clean of any social or political messiness, much as the life of the Bloom family, notwithstanding Will's poutiness, has been burnished to a warm, happy glow. In their eagerness to celebrate Edward's grand spirit, the filmmakers wind up diminishing it, declining to explore the causes or the costs of his addiction to fantasy.

In the past Mr. Burton's images have had a touch of the uncanny, as though they were windows onto the scary, marvelous landscape of the unconscious. ''Big Fish'' lacks the resonance of his earlier work partly because this time the bright, antic inventions are a form of denial. The film insists on viewing its hero as an affectionate, irrepressible raconteur. From where I sat, he looked more like an incorrigible narcissist and also, perhaps, a compulsive liar, whose love for others is little more than overflowing self-infatuation. But all this might be forgivable -- everyone else in the picture thinks so -- if Edward were not also a bit of a bore.

NYT

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:30

(A review of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 22 February 2012 10:30

(A review of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory)As Willy Wonka in Tim Burton's film of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Johnny Depp wears his hair in a bob that looks like he might have stolen it from Julie Christie in 1966, and he has milky translucent skin that gives him the appearance of a corpse made entirely of Muenster cheese. When he smiles, flashing teeth that are white and pearly enough to terrify Tony Robbins, it's less an invitation than a threat, as if his entire mouth were filled with fangs. Wearing a top hat and red velvet coat, speaking in a light effeminate voice of extreme fussiness, he looks and acts like a 19th-century vampire who is halfway through a sex change.

Wonka, the legendary candy maker, may be a stone freak, but he is also one of Burton's classic crackpot conjurers, like Beetlejuice or Ed Wood. Depp gives a performance that's an acrid, mocking put-on, delivering meta-sarcasms as if they were vicious tidbits meant only for his private amusement. At first, I thought he was doing his version of a manic Jim Carrey clown, surfing the channels of his own brain, but Depp, in his stylized way, never breaks character, never goes for the easy self-referential multimedia gag. He maintains the paradox, the mystery, of Willy Wonka: a misanthrope who has little patience for children, who can't even utter the word ''parents'' without gagging, yet who invents for those same kids the purest and most luscious candies out of the sugar dream of his imagination.

It's become an uncomfortable experience in movies to watch Burton, the prankish mod-goth fantasist, working to twist himself into ''mainstream'' shapes. His last two films, Big Fish and Planet of the Apes, lurched in and out of formula, but Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which has been faithfully adapted from Roald Dahl's great 1964 children's novel, is a delectably sustained flight of fancy. It's filled with puckish, deranged Burton touches, like the all-singing, all-melting puppets that herald Wonka's arrival, but it's also a grand and transporting celebration of the primal pleasures of childhood — namely, family and candy. As Wonka gives five children, who have all found his Golden Tickets, a tour of his famous factory, with its edible garden and chocolate waterfall, its kooky sci-fi chambers for testing out revolutionary new delights, he makes no secret of the fact that with the possible exception of Charlie (Freddie Highmore), a modest English lad as gracious as he is poor, he despises them all. He has good reason: The other children are brats, pigs, rich little bullies of entitlement. Burton gives us acidly funny new versions of the spoiled-rotten monsters you may remember from the 1971 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory — big babies like the German porker Augustus Gloop (Philip Wiegratz), the spiteful princess Veruca Salt (Julia Winter), and the television (now videogame) sociopath Mike Teavee (Jordan Fry). If anything, they seem timelier now, in an era when so many kids do get everything they want. As Wonka vents his disdain, though, it's still a comic shock to see an adult interact with children as if they were something he'd prefer to be roasting on a spit.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory revives, in a sassier but more artful way, the pixilated whimsy of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. The earlier film was driven, of course, by the creepy cuddliness of Gene Wilder — the smile of cozy dimpled warmth giving way to hysteria, then snapping back. Burton and Depp push Wonka further, making him into a sinister enigma, and in flashbacks to his childhood we see how he got that way: His father (Christopher Lee), a dentist, treated candy like poison and forced the boy to wear a torture chamber of a head brace. If that all sounds a bit Freudian, what it does is turn the entire film into a fairy-tale meditation on our relationship to candy: why it's wrong to love it too little, or too much.

As the children are vanquished, one by one, from the chocolate factory, each done in by greedy overindulgence, Burton makes the factory a place of blooming danger and wonder. The army of live squirrels shelling walnuts, the sight of Violet blowing up into a blueberry — these are indelible Burton images. The director also has a blast reinventing Wonka's army of pint-size assistants, the Oompa-Loompas. All of them are played, with digital replication, by Deep Roy, who looks like the deadpan maître d' of an Indian restaurant, and they appear in songs of various styles and eras (Esther Williams, psychedelic rock), scored with catchy deviltry by Danny Elfman. Those Oompa-Loompas are the beat, and soul, of Burton's finest movie since Ed Wood: a madhouse kiddie musical with a sweet-and-sour heart.

EW

Wonka, the legendary candy maker, may be a stone freak, but he is also one of Burton's classic crackpot conjurers, like Beetlejuice or Ed Wood. Depp gives a performance that's an acrid, mocking put-on, delivering meta-sarcasms as if they were vicious tidbits meant only for his private amusement. At first, I thought he was doing his version of a manic Jim Carrey clown, surfing the channels of his own brain, but Depp, in his stylized way, never breaks character, never goes for the easy self-referential multimedia gag. He maintains the paradox, the mystery, of Willy Wonka: a misanthrope who has little patience for children, who can't even utter the word ''parents'' without gagging, yet who invents for those same kids the purest and most luscious candies out of the sugar dream of his imagination.

It's become an uncomfortable experience in movies to watch Burton, the prankish mod-goth fantasist, working to twist himself into ''mainstream'' shapes. His last two films, Big Fish and Planet of the Apes, lurched in and out of formula, but Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which has been faithfully adapted from Roald Dahl's great 1964 children's novel, is a delectably sustained flight of fancy. It's filled with puckish, deranged Burton touches, like the all-singing, all-melting puppets that herald Wonka's arrival, but it's also a grand and transporting celebration of the primal pleasures of childhood — namely, family and candy. As Wonka gives five children, who have all found his Golden Tickets, a tour of his famous factory, with its edible garden and chocolate waterfall, its kooky sci-fi chambers for testing out revolutionary new delights, he makes no secret of the fact that with the possible exception of Charlie (Freddie Highmore), a modest English lad as gracious as he is poor, he despises them all. He has good reason: The other children are brats, pigs, rich little bullies of entitlement. Burton gives us acidly funny new versions of the spoiled-rotten monsters you may remember from the 1971 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory — big babies like the German porker Augustus Gloop (Philip Wiegratz), the spiteful princess Veruca Salt (Julia Winter), and the television (now videogame) sociopath Mike Teavee (Jordan Fry). If anything, they seem timelier now, in an era when so many kids do get everything they want. As Wonka vents his disdain, though, it's still a comic shock to see an adult interact with children as if they were something he'd prefer to be roasting on a spit.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory revives, in a sassier but more artful way, the pixilated whimsy of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. The earlier film was driven, of course, by the creepy cuddliness of Gene Wilder — the smile of cozy dimpled warmth giving way to hysteria, then snapping back. Burton and Depp push Wonka further, making him into a sinister enigma, and in flashbacks to his childhood we see how he got that way: His father (Christopher Lee), a dentist, treated candy like poison and forced the boy to wear a torture chamber of a head brace. If that all sounds a bit Freudian, what it does is turn the entire film into a fairy-tale meditation on our relationship to candy: why it's wrong to love it too little, or too much.

As the children are vanquished, one by one, from the chocolate factory, each done in by greedy overindulgence, Burton makes the factory a place of blooming danger and wonder. The army of live squirrels shelling walnuts, the sight of Violet blowing up into a blueberry — these are indelible Burton images. The director also has a blast reinventing Wonka's army of pint-size assistants, the Oompa-Loompas. All of them are played, with digital replication, by Deep Roy, who looks like the deadpan maître d' of an Indian restaurant, and they appear in songs of various styles and eras (Esther Williams, psychedelic rock), scored with catchy deviltry by Danny Elfman. Those Oompa-Loompas are the beat, and soul, of Burton's finest movie since Ed Wood: a madhouse kiddie musical with a sweet-and-sour heart.

EW

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 19 February 2012 08:42

(A review of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 19 February 2012 08:42

(A review of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo)Tiny as a sparrow, fierce as an eagle, Lisbeth Salander is one of the great Scandinavian avengers of our time, an angry bird catapulting into the fortresses of power and wiping smiles off the faces of smug, predatory pigs. The animating force in Stieg Larsson’s “Millennium” trilogy — incarnated on screen first by Noomi Rapace and now, in David Fincher’s adaptation of “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” by Rooney Mara — Lisbeth is an outlaw feminist fantasy-heroine, and also an avatar of digital antiauthoritarianism.

Her appeal arises from a combination of vulnerability and ruthless competence. Lisbeth can hack any machine, crack any code and, when necessary, mete out righteous punitive violence, but she is also (to an extent fully revealed in subsequent episodes) a lost and abused child. And Ms. Mara captures her volatile and fascinating essence beautifully. Hurt, fury and calculation play on her pierced and shadowed face. The black bangs across her forehead are as sharp and severe as an obsidian blade, but her eyebrows are as downy and pale as a baby’s. Lisbeth inspires fear and awe and also — on the part of Larsson and his fictional alter ego, the crusading journalist Mikael Blomkvist (played in Mr. Fincher’s film by Daniel Craig) — a measure of chivalrous protectiveness.

She is a marvelous pop-culture character, stranger and more complex than the average superhero and more intriguing than the usual boy wizards and vampire brides. It has been her fate, unfortunately, to make her furious, inspiring way through a series of plodding and ungainly stories.

The Swedish screen version of “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” directed by Niels Arden Oplev, often felt like the very long pilot episode of a television crime show, partly because of Larsson’s heavy-footed clumsiness as a storyteller. Despite the slick intensity of Mr. Fincher’s style, his movie is not immune to the same lumbering proceduralism. There are waves of brilliantly orchestrated anxiety and confusion but also long stretches of drab, hackneyed exposition that flatten the atmosphere. We might be watching “Cold Case” or “Criminal Minds,” but with better sound design and more expressive visual techniques. Hold your breath, it’s a time for a high-speed Internet search! Listen closely, because the chief bad guy is about to explain everything right before he kills you!

It must be said that Mr. Fincher and the screenwriter, Steven Zaillian, manage to hold on to the vivid and passionate essence of the book while remaining true enough to its busy plot to prevent literal-minded readers from rioting. (There are a few significant changes, but these show only how arbitrary some of Larsson’s narrative contrivances were in the first place.) Using harsh and spooky soundtrack music (by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross) to unnerving and powerful effect, Mr. Fincher creates a persuasive ambience of political menace and moral despair.

He has always excelled at evoking invisible, nonspecific terrors lurking just beyond the realm of the visible. The San Francisco of “Zodiac” was haunted not so much by an elusive serial killer as by a spectral principle of violence that was everywhere and nowhere, a sign of the times and an element of the climate. And the Harvard of “The Social Network,” with its darkened wood and moody brick, seemed less a preserve of gentlemen and scholars than a seething hive of paranoia and alienation.

Mr. Fincher honors Larsson’s muckraking legacy by envisioning a Sweden that is corrupt not merely in its ruling institutions but in the depths of its soul. Lisbeth and Mikael — whose first meeting comes around the midpoint of the movie’s 158-minutes — swim in a sea of rottenness. They are not quite the only decent people in the country, but their enemies are so numerous, so powerful and so deeply entrenched that the odds of defeating them seem overwhelming.

Mikael, his career in ruins and his gadfly magazine in jeopardy after a libel judgment, is hired by a wealthy industrialist, Henrik Vanger (Christopher Plummer), to investigate a decades-old crime. Dysfunction would be a step up for the Vanger clan, who live on a secluded island and whose family tree includes Nazis, rapists, alcoholics, murderers and also, just to prevent you from getting the wrong impression, Stellan Skarsgard, the very epitome of Nordic nastiness.

The Vangers are monstrous, with a few exceptions, but far from anomalous. The gruesome pattern of criminality that Lisbeth and Mikael uncover is a manifestation of general evil that spreads throughout the upper echelons of the nation’s economy and government. The bad apples in that family are just one face of a cruel, misogynist ruling order that also includes Bjurman (Yorick van Wageningen), the sadistic state bureaucrat who is Lisbeth’s legal guardian. And everywhere she and Mikael turn there are more bullying, unprincipled and abusive men.

Sexual violence is a lurid thread running through “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” and Mr. Fincher approaches it with queasy, teasing sensationalism. Lisbeth’s dealings with Bjurman include a vicious rape and a correspondingly brutal act of revenge, and there is something prurient and salacious about the way the initial assault is filmed. The vengeance, while graphic, is visually more circumspect.

And when Mikael and Lisbeth interrupt their sleuthing for a bit of nonviolent sex, we see all of Ms. Mara and quite a bit less of Mr. Craig, whose naked torso is by now an eyeful of old news. This disparity is perfectly conventional — the exploitation of female nudity is an axiom of modern cinema — but it also represents a failure of nerve and a betrayal of the sexual egalitarianism Lisbeth Salander argues for and represents.

Still, it is her movie, and Ms. Mara’s. Mr. Craig is an obliging sidekick, and the other supporting actors (notably Robin Wright as Mikael’s colleague and paramour and Donald Sumpter as a helpful detective) perform with professionalism and conviction. Mr. Fincher’s impressive skill is evident, even as his ambitions seem to be checked by the limitations of the source material and the imperatives of commercial entertainment.

There is too much data and not enough insight, and local puzzles that get in the way of larger mysteries. The story starts to fade as soon as the end credits run. But it is much harder to shake the lingering, troubling memory of an angry, elusive and curiously magnetic young woman who belongs so completely to this cynical, cybernetic and chaotic world without ever seeming to be at home in it.

NYT

Her appeal arises from a combination of vulnerability and ruthless competence. Lisbeth can hack any machine, crack any code and, when necessary, mete out righteous punitive violence, but she is also (to an extent fully revealed in subsequent episodes) a lost and abused child. And Ms. Mara captures her volatile and fascinating essence beautifully. Hurt, fury and calculation play on her pierced and shadowed face. The black bangs across her forehead are as sharp and severe as an obsidian blade, but her eyebrows are as downy and pale as a baby’s. Lisbeth inspires fear and awe and also — on the part of Larsson and his fictional alter ego, the crusading journalist Mikael Blomkvist (played in Mr. Fincher’s film by Daniel Craig) — a measure of chivalrous protectiveness.

She is a marvelous pop-culture character, stranger and more complex than the average superhero and more intriguing than the usual boy wizards and vampire brides. It has been her fate, unfortunately, to make her furious, inspiring way through a series of plodding and ungainly stories.

The Swedish screen version of “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” directed by Niels Arden Oplev, often felt like the very long pilot episode of a television crime show, partly because of Larsson’s heavy-footed clumsiness as a storyteller. Despite the slick intensity of Mr. Fincher’s style, his movie is not immune to the same lumbering proceduralism. There are waves of brilliantly orchestrated anxiety and confusion but also long stretches of drab, hackneyed exposition that flatten the atmosphere. We might be watching “Cold Case” or “Criminal Minds,” but with better sound design and more expressive visual techniques. Hold your breath, it’s a time for a high-speed Internet search! Listen closely, because the chief bad guy is about to explain everything right before he kills you!

It must be said that Mr. Fincher and the screenwriter, Steven Zaillian, manage to hold on to the vivid and passionate essence of the book while remaining true enough to its busy plot to prevent literal-minded readers from rioting. (There are a few significant changes, but these show only how arbitrary some of Larsson’s narrative contrivances were in the first place.) Using harsh and spooky soundtrack music (by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross) to unnerving and powerful effect, Mr. Fincher creates a persuasive ambience of political menace and moral despair.

He has always excelled at evoking invisible, nonspecific terrors lurking just beyond the realm of the visible. The San Francisco of “Zodiac” was haunted not so much by an elusive serial killer as by a spectral principle of violence that was everywhere and nowhere, a sign of the times and an element of the climate. And the Harvard of “The Social Network,” with its darkened wood and moody brick, seemed less a preserve of gentlemen and scholars than a seething hive of paranoia and alienation.

Mr. Fincher honors Larsson’s muckraking legacy by envisioning a Sweden that is corrupt not merely in its ruling institutions but in the depths of its soul. Lisbeth and Mikael — whose first meeting comes around the midpoint of the movie’s 158-minutes — swim in a sea of rottenness. They are not quite the only decent people in the country, but their enemies are so numerous, so powerful and so deeply entrenched that the odds of defeating them seem overwhelming.

Mikael, his career in ruins and his gadfly magazine in jeopardy after a libel judgment, is hired by a wealthy industrialist, Henrik Vanger (Christopher Plummer), to investigate a decades-old crime. Dysfunction would be a step up for the Vanger clan, who live on a secluded island and whose family tree includes Nazis, rapists, alcoholics, murderers and also, just to prevent you from getting the wrong impression, Stellan Skarsgard, the very epitome of Nordic nastiness.

The Vangers are monstrous, with a few exceptions, but far from anomalous. The gruesome pattern of criminality that Lisbeth and Mikael uncover is a manifestation of general evil that spreads throughout the upper echelons of the nation’s economy and government. The bad apples in that family are just one face of a cruel, misogynist ruling order that also includes Bjurman (Yorick van Wageningen), the sadistic state bureaucrat who is Lisbeth’s legal guardian. And everywhere she and Mikael turn there are more bullying, unprincipled and abusive men.

Sexual violence is a lurid thread running through “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” and Mr. Fincher approaches it with queasy, teasing sensationalism. Lisbeth’s dealings with Bjurman include a vicious rape and a correspondingly brutal act of revenge, and there is something prurient and salacious about the way the initial assault is filmed. The vengeance, while graphic, is visually more circumspect.

And when Mikael and Lisbeth interrupt their sleuthing for a bit of nonviolent sex, we see all of Ms. Mara and quite a bit less of Mr. Craig, whose naked torso is by now an eyeful of old news. This disparity is perfectly conventional — the exploitation of female nudity is an axiom of modern cinema — but it also represents a failure of nerve and a betrayal of the sexual egalitarianism Lisbeth Salander argues for and represents.

Still, it is her movie, and Ms. Mara’s. Mr. Craig is an obliging sidekick, and the other supporting actors (notably Robin Wright as Mikael’s colleague and paramour and Donald Sumpter as a helpful detective) perform with professionalism and conviction. Mr. Fincher’s impressive skill is evident, even as his ambitions seem to be checked by the limitations of the source material and the imperatives of commercial entertainment.

There is too much data and not enough insight, and local puzzles that get in the way of larger mysteries. The story starts to fade as soon as the end credits run. But it is much harder to shake the lingering, troubling memory of an angry, elusive and curiously magnetic young woman who belongs so completely to this cynical, cybernetic and chaotic world without ever seeming to be at home in it.

NYT

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Hangover: Part II review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 19 February 2012 04:15

(A review of The Hangover: Part II)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 19 February 2012 04:15

(A review of The Hangover: Part II)A shaved head. A severed finger. A Bangkok hotel room that's cruddy enough to be a crack den. A screaming monkey in a Rolling Stones blue-jean vest. A Mike Tyson Maori tattoo freshly etched around the eye of Stu (Ed Helms), the polite dentist who's the one getting married this time. In The Hangover Part II, the cleverly structured, pretty funny sequel to Todd Phillips' 2009 what-happens-in-Vegas megahit The Hangover, those are the mysterious WTF clues to whatever happened the night before to sharkish, presentable Phil (Bradley Cooper), reckless half-wit Alan (Zach Galifianakis), and sweet, repressed Stu. Once again, the characters — and the audience — have to work backward to find out what, exactly, put the trio known as the Wolfpack in this sorry and dazed predicament. And once again, the movie hypes the sleazy, dangerous thrill of three ordinary schmoes on a bender and shrewdly domesticates it at the same time.

This much we know: They all traveled to a seaside resort in Thailand for Stu's wedding to Lauren (Jamie Chung), whose father hates his future son-in-law so much that during a toast at the rehearsal dinner, he pays him a ''compliment'' by comparing him to comfortably plain, soggy white rice. (That's just the kind of goofy-misanthropic '80s-style joke that Phillips thrives on.) Stu, having learned about the perils of intoxication in The Hangover after he extracted one of his own incisors, insists on no bachelor party. And so the trio, accompanied by Lauren's studious teenage brother, Teddy (Mason Lee), meet on the beach for a campfire and a beer…but end up in this post-mayhem dilemma anyway. The next day, Teddy is nowhere to be found (though that sliced-off digit appears to be his). But the guys do find Mr. Chow, the English-mangling gangster played in both films by Ken Jeong with such wackadoo exuberance that you can almost forgive the slight racism of the character. (Let's be honest: He's a badass version of Long Duk Dong from Sixteen Candles.) Chow is now practically part of the Wolfpack himself — at least until he takes a snort of cocaine and collapses.

Here, as in The Hangover, the laughs aren't just staged, they're superlatively engineered — even if that means, at moments, that they feel like they're falling into formatted slots. When they don't, the movie can be flat-out hilarious. As the guys begin their desperate search for a missing bank account number (they have to give it to a drug lord or he'll kill them), it's no surprise to discover that they went to a Bangkok strip bar. And when we learn what happened in that club to Stu — who hasn't shaken his tendency to fall drunkenly head over heels in love with hookers — you may see the twist coming, but you won't foresee the casual outrageousness of the dialogue, the kind that keeps on giving.

Yet that sort of choke-on-your-popcorn laugh is more the exception than the rule. Like the first film, The Hangover Part II comes on as a slapstick orgy of naughtiness, but beneath that, the movie is a reassuringly conventional comic detective story in which most of the fun lies in piecing the evidence of debauchery together. And that, at least to me, tends to produce chuckles rather than major guffaws. Still, Phillips keeps the whole thing popping, and the clogged, smoggy Bangkok setting, with its layered skeeziness and depravity, lends the picture a vivid squalor that grounds the laughs in reality a notch more than Vegas did. On those festering streets of sin, anything can happen — and does. Paul Giamatti screams (winningly) as a big-shot crime boss, and a car chase is as madly jacked as the one in Doug Liman's Go.

Now that we know them, the core characters are all the funnier; they've become an American suburban version of the Three Stooges. Cooper, the voice of exasperated sanity, plays Phil with great addled double takes, and Helms, as the frazzled, neurotic Stu, puts his rage and anxiety gleefully close to the surface. Even more than before, Zach Galifianakis is the wild card. Looking like a prison-camp mongrel with his shaved head, he makes Alan an overgrown damaged child with a screw loose: You never know what he'll say next, yet somehow it all connects. I wouldn't call The Hangover Part II a message movie, but it has a saucy, redemptive vibe: It says that sometimes the only way to grow up is to act as badly as you possibly can and come out the other side. And to vow — nudge, nudge — never to do it again. B+

This much we know: They all traveled to a seaside resort in Thailand for Stu's wedding to Lauren (Jamie Chung), whose father hates his future son-in-law so much that during a toast at the rehearsal dinner, he pays him a ''compliment'' by comparing him to comfortably plain, soggy white rice. (That's just the kind of goofy-misanthropic '80s-style joke that Phillips thrives on.) Stu, having learned about the perils of intoxication in The Hangover after he extracted one of his own incisors, insists on no bachelor party. And so the trio, accompanied by Lauren's studious teenage brother, Teddy (Mason Lee), meet on the beach for a campfire and a beer…but end up in this post-mayhem dilemma anyway. The next day, Teddy is nowhere to be found (though that sliced-off digit appears to be his). But the guys do find Mr. Chow, the English-mangling gangster played in both films by Ken Jeong with such wackadoo exuberance that you can almost forgive the slight racism of the character. (Let's be honest: He's a badass version of Long Duk Dong from Sixteen Candles.) Chow is now practically part of the Wolfpack himself — at least until he takes a snort of cocaine and collapses.

Here, as in The Hangover, the laughs aren't just staged, they're superlatively engineered — even if that means, at moments, that they feel like they're falling into formatted slots. When they don't, the movie can be flat-out hilarious. As the guys begin their desperate search for a missing bank account number (they have to give it to a drug lord or he'll kill them), it's no surprise to discover that they went to a Bangkok strip bar. And when we learn what happened in that club to Stu — who hasn't shaken his tendency to fall drunkenly head over heels in love with hookers — you may see the twist coming, but you won't foresee the casual outrageousness of the dialogue, the kind that keeps on giving.

Yet that sort of choke-on-your-popcorn laugh is more the exception than the rule. Like the first film, The Hangover Part II comes on as a slapstick orgy of naughtiness, but beneath that, the movie is a reassuringly conventional comic detective story in which most of the fun lies in piecing the evidence of debauchery together. And that, at least to me, tends to produce chuckles rather than major guffaws. Still, Phillips keeps the whole thing popping, and the clogged, smoggy Bangkok setting, with its layered skeeziness and depravity, lends the picture a vivid squalor that grounds the laughs in reality a notch more than Vegas did. On those festering streets of sin, anything can happen — and does. Paul Giamatti screams (winningly) as a big-shot crime boss, and a car chase is as madly jacked as the one in Doug Liman's Go.

Now that we know them, the core characters are all the funnier; they've become an American suburban version of the Three Stooges. Cooper, the voice of exasperated sanity, plays Phil with great addled double takes, and Helms, as the frazzled, neurotic Stu, puts his rage and anxiety gleefully close to the surface. Even more than before, Zach Galifianakis is the wild card. Looking like a prison-camp mongrel with his shaved head, he makes Alan an overgrown damaged child with a screw loose: You never know what he'll say next, yet somehow it all connects. I wouldn't call The Hangover Part II a message movie, but it has a saucy, redemptive vibe: It says that sometimes the only way to grow up is to act as badly as you possibly can and come out the other side. And to vow — nudge, nudge — never to do it again. B+

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Just Like Heaven review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 19 February 2012 04:12

(A review of Just Like Heaven)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 19 February 2012 04:12

(A review of Just Like Heaven)Telling a friend you’ve set her up on a date with a sweet guy who has a good personality is like giving the dating candidate the kiss of death. But thankfully there’s no such stigma attached to the word 'sweet' when it's used to describe a romantic comedy. “Just Like Heaven” is the movie equivalent of a harmless first date: polite and sweet. It's a pleasant enough way to spend an evening, yet ultimately totally forgettable.

“Just Like Heaven” doesn’t try to reinvent the romantic comedy genre. It sticks to the old formula of boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy fights to get girl back. The only thing that sets this rom com apart is the talented cast and the plot twist of having the female lead portray a ghost.

Reese Witherspoon stars as Elizabeth, a workaholic doctor who has no social life, no friends other than acquaintances at work, and no romantic entanglements. As a doctor competing for a residency position with a butt kissing suck up (played with smarmy charm by Ben Shenkman), Elizabeth survives on lots of caffeine and a determination to be the best. But her 'survival' is soon an issue when, while distracted driving home, she crashes her car into a big rig.

Mark Ruffalo enters the picture as David, a former landscape designer who recently suffered through life-altering upheaval of his own. Subletting an apartment in San Francisco (he selected it based solely on the furnished apartment’s comfy couch), David now spends his days and nights flipping through TV channels, guzzling beer, munching on fast food, and generally moping around. Not wanting to be bothered, David tucks himself away from life by spending the majority of his time safely inside his rented apartment.

But David’s cozy apartment soon becomes a little crowded. Elizabeth shows up out of the blue, claiming the place is hers (which it is) and that he has no right to be there (which he does). David figures he’s either crazy or he’s being haunted by a very unpleasant, pushy ghost. Deciding it’s the latter, he tries his best to get Elizabeth to go into the light. When that doesn’t work, the two make an uneasy truce. Together they try and figure out what happened to Elizabeth, whose skills now include walking through walls and other ghostly feats, and why her ghost can only be seen by David.

Since this is a romantic comedy and because the eventual outcome is telegraphed from the start (and in the movie’s trailer), you know these two are going to wind up falling for one another despite the fact that, as a ghost, Elizabeth is unable to touch anything. How they work things out and what they have to overcome to get there is what makes “Just Like Heaven” such a cute little feel-good, fluffball comedy.

The two leads are adorable. Even when Mark Ruffalo’s character is at his frumpiest (as called for in the script), the actor can’t help but look sweetly attractive. Reese Witherspoon once again proves she’s a sure thing when it comes to casting romantic comedies. She can pull off things others of her generation would look silly trying to attempt. And let’s face it, Witherspoon is this generation’s Meg Ryan - whether she wants to be or not. I say that with the following caveat: Witherspoon’s only comparable to Ryan as far as romantic comedies are concerned. Witherspoon’s dramatic skills are much more advanced than Ryan’s were at the same age. Witherspoon also does darker comedy better than Ryan ever did.

Jon Heder follows up his breakthrough performance in “Napoleon Dynamite” with a supporting role in “Just Like Heaven.” Playing the owner of an occult book store, Heder’s character provides a link between the living and the dead. His character also generates a large dose of laughs. In fact, the preview audience I was with actually laughed as soon as Heder’s face appeared onscreen. He didn’t even have to utter a line to win the audience over.

“Just Like Heaven” isn’t a movie meant to be dissected by critics. The effects are decent but not groundbreaking. Lighting, locations, and other technical issues play no part in making or breaking this romantic comedy. It is what it is: a fluffy escapist movie.

“Just Like Heaven” doesn’t try to reinvent the romantic comedy genre. It sticks to the old formula of boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy fights to get girl back. The only thing that sets this rom com apart is the talented cast and the plot twist of having the female lead portray a ghost.

Reese Witherspoon stars as Elizabeth, a workaholic doctor who has no social life, no friends other than acquaintances at work, and no romantic entanglements. As a doctor competing for a residency position with a butt kissing suck up (played with smarmy charm by Ben Shenkman), Elizabeth survives on lots of caffeine and a determination to be the best. But her 'survival' is soon an issue when, while distracted driving home, she crashes her car into a big rig.

Mark Ruffalo enters the picture as David, a former landscape designer who recently suffered through life-altering upheaval of his own. Subletting an apartment in San Francisco (he selected it based solely on the furnished apartment’s comfy couch), David now spends his days and nights flipping through TV channels, guzzling beer, munching on fast food, and generally moping around. Not wanting to be bothered, David tucks himself away from life by spending the majority of his time safely inside his rented apartment.

But David’s cozy apartment soon becomes a little crowded. Elizabeth shows up out of the blue, claiming the place is hers (which it is) and that he has no right to be there (which he does). David figures he’s either crazy or he’s being haunted by a very unpleasant, pushy ghost. Deciding it’s the latter, he tries his best to get Elizabeth to go into the light. When that doesn’t work, the two make an uneasy truce. Together they try and figure out what happened to Elizabeth, whose skills now include walking through walls and other ghostly feats, and why her ghost can only be seen by David.

Since this is a romantic comedy and because the eventual outcome is telegraphed from the start (and in the movie’s trailer), you know these two are going to wind up falling for one another despite the fact that, as a ghost, Elizabeth is unable to touch anything. How they work things out and what they have to overcome to get there is what makes “Just Like Heaven” such a cute little feel-good, fluffball comedy.

The two leads are adorable. Even when Mark Ruffalo’s character is at his frumpiest (as called for in the script), the actor can’t help but look sweetly attractive. Reese Witherspoon once again proves she’s a sure thing when it comes to casting romantic comedies. She can pull off things others of her generation would look silly trying to attempt. And let’s face it, Witherspoon is this generation’s Meg Ryan - whether she wants to be or not. I say that with the following caveat: Witherspoon’s only comparable to Ryan as far as romantic comedies are concerned. Witherspoon’s dramatic skills are much more advanced than Ryan’s were at the same age. Witherspoon also does darker comedy better than Ryan ever did.

Jon Heder follows up his breakthrough performance in “Napoleon Dynamite” with a supporting role in “Just Like Heaven.” Playing the owner of an occult book store, Heder’s character provides a link between the living and the dead. His character also generates a large dose of laughs. In fact, the preview audience I was with actually laughed as soon as Heder’s face appeared onscreen. He didn’t even have to utter a line to win the audience over.

“Just Like Heaven” isn’t a movie meant to be dissected by critics. The effects are decent but not groundbreaking. Lighting, locations, and other technical issues play no part in making or breaking this romantic comedy. It is what it is: a fluffy escapist movie.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Resident Evil: Extinction review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 15 February 2012 11:05

(A review of Resident Evil: Extinction)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 15 February 2012 11:05

(A review of Resident Evil: Extinction)Resident Evil: Extinction is the third film in this zombie franchise, so let’s take a minute to figure out where we’re at. The first Resident Evil was a blast due in part to blind stupid luck, and in greater part an ensemble cast containing, in addition to Milla Jovovich, Michelle Rodriguez in her last good performance before becoming that alcoholic from TV’s Lost. The second one fell flat on its ass; Paul W.S. Anderson’s script was a mess and Alexander Witt, the guy they hired to direct it, managed to make it even worse. For Extinction, they’ve brought in helmer Russell Mulcahy who takes another terrible Paul W.S. Anderson screenplay and redeems the franchise by hitting it out of the park.

Like the others in this series, Resident Evil: Extinction is an action movie first, and a zombie movie second. Milla Jovovich’s Alice character could be fighting anything, it doesn’t have to be zombies, that just happens to be what they’ve settled on for this particular set of stories. And that’s fine, since zombies have been done to death and I for one am getting sick of watching them. Resident Evil: Extinction doesn’t need to be a good zombie movie, or even a good horror movie in order to work. It does however need to be fast-paced and fun; thankfully Mulcahy pulls that off admirably.

It’s five years since the last Resident Evil movie, and things have gone badly. The zombie-making virus unleashed in the first movie has since spread across the entire planet, turning the world into a wasteland desert inhabited by mindless, flesh-eating baddies. On the surface, only a few ragtag bands of humans survive. To live they must keep on the move, if they stop the undead flock to them and chow down. Underground, the evil Umbrella corporation still exists. You remember them, the all powerful capitalist monolith which created the zombie virus in the first place and in the past worried more about its profit margins than saving the human race. Now they’ve all retreated to underground bunkers where they create and kill clones of Alice in an attempt to find a cure for that which ails the world, or at least a way to make things better for themselves. After watching her beat the hell out of everything in the first and second movies, they believe Alice is the key, and so they’d love to get their hands on the original.

The original Alice we know and love is one of the few people left living on the surface, and like everyone else she’s on the move. She joins up with a convoy of survivors traveling Road Warrior style, and attempts to help their leader Claire take them to Alaska where rumor has it, the infection hasn’t spread. The movie works surprisingly well early on as a post-apocalyptic survival tale. I’m not kidding with that Road Warrior comparison, there are definitely moments when the film nearly has a sweet Mad Max vibe going for it, or at least a little bit of Thunderdome. Sadly, it doesn’t last and soon those Umbrellla Corporation bastards get in the way, ruining the survivor’s zombie smashing run to the Great White North.

What’s most surprising about Extinction is how tame the franchise has become. The film is rated-R, but only barely. I had to go home and look it up, because it plays like it’s PG-13. Gone is the now trademark Milla Jovovich full-frontal nudity which usually graces these movies. The film is also pretty light on zombie decapitations. Evidently you now only need to slash their throats in order to kill them, presumably because that’s less gruesome than chopping off heads. This would make sense if they were bucking for a PG-13, but the movie is R so you’ve got to wonder why they didn’t take it all the way.

Speaking of taking it all the way, it wouldn’t have hurt to make it longer either. It’s one thing to be fast paced, but it’s another to jump from scene to scene so fast that you’re left with silly coincidences and unbelievable logical gaps. The script is incredibly thin, and there really should be more to it. Pacing isn’t necessarily dictated by running time, and a few more minutes tacked on could have worked wonders for the film’s plot without sacrificing the quick beat Mulcahy sets for it. Extinction is good enough even as it is that I wouldn’t have minded spending more time with it.

Thin or not, Extinction is a fast, well staged action movie with giddy, creative sequences involving things like zombie birds and a genius moment in which Oded Fehr blows everything to hell while toking on a joint. More importantly, Milla still looks great doing her karate moves. Gone is some of the wildly over-the-top, annoying action prevalent in the second film. This time when Milla strikes her superhero pose, you’re cheering for her instead of wondering how the hell she managed to suddenly become Spider-Man. The script is undeniably shoddy, full of wild coincidences and it often seems more concerned with setting things up for yet another sequel than finishing the film at hand. The end in particular suffers from that, the movie’s finale seems like rush to get to the franchise’s next movie rather than a big finish to this one. Still Mulcahy and his cast overcome all of that to delivery an enjoyable experience, back in the twisting, zombie-infested levels of the Resident Evil world.

Like the others in this series, Resident Evil: Extinction is an action movie first, and a zombie movie second. Milla Jovovich’s Alice character could be fighting anything, it doesn’t have to be zombies, that just happens to be what they’ve settled on for this particular set of stories. And that’s fine, since zombies have been done to death and I for one am getting sick of watching them. Resident Evil: Extinction doesn’t need to be a good zombie movie, or even a good horror movie in order to work. It does however need to be fast-paced and fun; thankfully Mulcahy pulls that off admirably.

It’s five years since the last Resident Evil movie, and things have gone badly. The zombie-making virus unleashed in the first movie has since spread across the entire planet, turning the world into a wasteland desert inhabited by mindless, flesh-eating baddies. On the surface, only a few ragtag bands of humans survive. To live they must keep on the move, if they stop the undead flock to them and chow down. Underground, the evil Umbrella corporation still exists. You remember them, the all powerful capitalist monolith which created the zombie virus in the first place and in the past worried more about its profit margins than saving the human race. Now they’ve all retreated to underground bunkers where they create and kill clones of Alice in an attempt to find a cure for that which ails the world, or at least a way to make things better for themselves. After watching her beat the hell out of everything in the first and second movies, they believe Alice is the key, and so they’d love to get their hands on the original.

The original Alice we know and love is one of the few people left living on the surface, and like everyone else she’s on the move. She joins up with a convoy of survivors traveling Road Warrior style, and attempts to help their leader Claire take them to Alaska where rumor has it, the infection hasn’t spread. The movie works surprisingly well early on as a post-apocalyptic survival tale. I’m not kidding with that Road Warrior comparison, there are definitely moments when the film nearly has a sweet Mad Max vibe going for it, or at least a little bit of Thunderdome. Sadly, it doesn’t last and soon those Umbrellla Corporation bastards get in the way, ruining the survivor’s zombie smashing run to the Great White North.

What’s most surprising about Extinction is how tame the franchise has become. The film is rated-R, but only barely. I had to go home and look it up, because it plays like it’s PG-13. Gone is the now trademark Milla Jovovich full-frontal nudity which usually graces these movies. The film is also pretty light on zombie decapitations. Evidently you now only need to slash their throats in order to kill them, presumably because that’s less gruesome than chopping off heads. This would make sense if they were bucking for a PG-13, but the movie is R so you’ve got to wonder why they didn’t take it all the way.

Speaking of taking it all the way, it wouldn’t have hurt to make it longer either. It’s one thing to be fast paced, but it’s another to jump from scene to scene so fast that you’re left with silly coincidences and unbelievable logical gaps. The script is incredibly thin, and there really should be more to it. Pacing isn’t necessarily dictated by running time, and a few more minutes tacked on could have worked wonders for the film’s plot without sacrificing the quick beat Mulcahy sets for it. Extinction is good enough even as it is that I wouldn’t have minded spending more time with it.

Thin or not, Extinction is a fast, well staged action movie with giddy, creative sequences involving things like zombie birds and a genius moment in which Oded Fehr blows everything to hell while toking on a joint. More importantly, Milla still looks great doing her karate moves. Gone is some of the wildly over-the-top, annoying action prevalent in the second film. This time when Milla strikes her superhero pose, you’re cheering for her instead of wondering how the hell she managed to suddenly become Spider-Man. The script is undeniably shoddy, full of wild coincidences and it often seems more concerned with setting things up for yet another sequel than finishing the film at hand. The end in particular suffers from that, the movie’s finale seems like rush to get to the franchise’s next movie rather than a big finish to this one. Still Mulcahy and his cast overcome all of that to delivery an enjoyable experience, back in the twisting, zombie-infested levels of the Resident Evil world.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

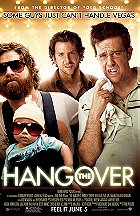

The Hangover review

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 15 February 2012 11:03

(A review of The Hangover)

Posted : 13 years, 4 months ago on 15 February 2012 11:03

(A review of The Hangover)Now this is what I'm talkin' about. "The Hangover" is a funny movie, flat out, all the way through. Its setup is funny. Every situation is funny. Most of the dialogue is funny almost line by line. At some point we actually find ourselves caring a little about what happened to the missing bridegroom -- and the fact that we almost care is funny, too.

The movie opens with bad news for a bride on her wedding day. Her fiance's best buddy is standing in the Mojave Desert with a bloody lip and three other guys, none of whom is her fiance. They've lost him. He advises her there's no way the wedding is taking place.

We flash back two days to their road trip to Vegas for a bachelor party. Doug, her future husband (Justin Bartha), will be joined by his two friends, the schoolteacher Phil (Bradley Cooper) and the dentist Stu (Ed Helms). Joining them will be her brother Alan (Zach Galifianakis), an overweight slob with a Haystacks Calhoun beard and an injunction against coming within 200 feet of a school building.

The next morning, Doug will be missing. The other three are missing for several hours; none of them can remember a thing since they were on the roof of Caesars Palace, drinking shots of Jagermeister. They would desperately like to know: How in the hell do you wake up in a $4,200-a-night suite with a tiger, a chicken, a crying baby, a missing tooth and a belly button pierced for a diamond dangle? And when you give your parking check to the doorman, why does he bring around a police car? And where is Doug?

Their search provides a structure for the rest of the movie, during a very long day that includes a fact-finding visit to a wedding chapel, a violent encounter with a small but very mean Chinese mobster, a sweet hooker, an interview with an emergency room doctor and an encounter with Mike Tyson, whose tiger they appear they have stolen, although under the circumstances, he is fairly nice about it. There is never an explanation for the chicken.

Despite these events, "The Hangover" isn't simply a laff riot. I won't go so far as to describe it as a character study, but all three men have profound personality problems, and the Vegas trip works on them like applied emergency therapy. The dentist is rigidly ruled by his bitchy girlfriend. The schoolteacher thinks nothing of stealing the money for a class trip. And Alan ...

Well, Zach Galifianakis' performance is the kind of breakout performance that made John Belushi a star after "Animal House." He is short, stocky, wants to be liked, has a yearning energy, was born clueless. It is a tribute to Galifianakis' acting that we actually believe he is sincere when he asks the clerk at the check-in counter: "Is this the real Caesars Palace? Does Caesar live here?"

"The Hangover" is directed by Todd Phillips, whose "Old School" (2003) and "Road Trip" (2000) had their moments but didn't prepare me for this. The screenplay is by Jon Lucas and Scott Moore, whose "Ghosts of Girlfriends Past" certainly didn't. This movie is written, not assembled out of off-the-shelf parts from the Apatow Surplus Store. There is a level of detail and observation in the dialogue that's sort of remarkable: These characters aren't generically funny, but specifically funny. The actors make them halfway convincing.

Phillips has them encountering a mixed bag of weird characters, which is standard, but the characters aren't. Mr. Chow (Ken Jeong), the vertically challenged naked man they find locked in the trunk of the police car, is strong, skilled in martial arts and really mean about Alan's obesity. He finds almost anything a fat man does to be hilarious. When he finds his clothes and his henchmen, he is not to be trifled with. Jade (Heather Graham), a stripper, is forthright: "Well, actually, I'm an escort, but stripping is a good way to meet clients." She isn't the good-hearted cliche, but more of a sincere young woman who would like to meet the right guy.

The search for Doug has the friends piecing together clues from the ER doctor, Mike Tyson's security tapes and a mattress that is impaled on the uplifted arm of one of the Caesars Palace statues. The plot hurtles through them.

If the movie ends somewhat conventionally, well, it almost has to; narrative housecleaning requires it. It begins conventionally, too, with uplifting music and a typeface for the titles that may remind you of "My Best Friend's Wedding." But it is not to be. Here is a movie that deserves every letter of its R rating. What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, especially after you throw up.

The movie opens with bad news for a bride on her wedding day. Her fiance's best buddy is standing in the Mojave Desert with a bloody lip and three other guys, none of whom is her fiance. They've lost him. He advises her there's no way the wedding is taking place.

We flash back two days to their road trip to Vegas for a bachelor party. Doug, her future husband (Justin Bartha), will be joined by his two friends, the schoolteacher Phil (Bradley Cooper) and the dentist Stu (Ed Helms). Joining them will be her brother Alan (Zach Galifianakis), an overweight slob with a Haystacks Calhoun beard and an injunction against coming within 200 feet of a school building.

The next morning, Doug will be missing. The other three are missing for several hours; none of them can remember a thing since they were on the roof of Caesars Palace, drinking shots of Jagermeister. They would desperately like to know: How in the hell do you wake up in a $4,200-a-night suite with a tiger, a chicken, a crying baby, a missing tooth and a belly button pierced for a diamond dangle? And when you give your parking check to the doorman, why does he bring around a police car? And where is Doug?

Their search provides a structure for the rest of the movie, during a very long day that includes a fact-finding visit to a wedding chapel, a violent encounter with a small but very mean Chinese mobster, a sweet hooker, an interview with an emergency room doctor and an encounter with Mike Tyson, whose tiger they appear they have stolen, although under the circumstances, he is fairly nice about it. There is never an explanation for the chicken.

Despite these events, "The Hangover" isn't simply a laff riot. I won't go so far as to describe it as a character study, but all three men have profound personality problems, and the Vegas trip works on them like applied emergency therapy. The dentist is rigidly ruled by his bitchy girlfriend. The schoolteacher thinks nothing of stealing the money for a class trip. And Alan ...

Well, Zach Galifianakis' performance is the kind of breakout performance that made John Belushi a star after "Animal House." He is short, stocky, wants to be liked, has a yearning energy, was born clueless. It is a tribute to Galifianakis' acting that we actually believe he is sincere when he asks the clerk at the check-in counter: "Is this the real Caesars Palace? Does Caesar live here?"

"The Hangover" is directed by Todd Phillips, whose "Old School" (2003) and "Road Trip" (2000) had their moments but didn't prepare me for this. The screenplay is by Jon Lucas and Scott Moore, whose "Ghosts of Girlfriends Past" certainly didn't. This movie is written, not assembled out of off-the-shelf parts from the Apatow Surplus Store. There is a level of detail and observation in the dialogue that's sort of remarkable: These characters aren't generically funny, but specifically funny. The actors make them halfway convincing.